No edit summary Tags: Source edit Mobile edit Mobile web edit |

No edit summary Tag: Source edit |

||

| Line 18: | Line 18: | ||

*Sivard |

*Sivard |

||

|Proto-Germanic = ''*Sigiwarduz'' |

|Proto-Germanic = ''*Sigiwarduz'' |

||

| + | |Runic = ᛋᛁᚴᚢᚱᚦᚱ <small>(Old Norse)</small> |

||

|English = Siward |

|English = Siward |

||

|Alias = Sigurðr "Fáfnisbana" Sigmundsson |

|Alias = Sigurðr "Fáfnisbana" Sigmundsson |

||

Revision as of 04:17, 25 February 2021

Sigurðr, Siegfried (Middle High German: Sîvrit) or Sigurd is a legendary hero of Norse mythology, as well as the central character in the Vǫlsunga saga. The earliest extant representations for his legend come in pictorial form from seven runestones in Sweden and most notably the Ramsund carving (c. 1000) and the Gök Runestone (11th century).

Etymology

The names Sigurd and Siegfried do not share the same etymology. Both have the same first element, Proto-Germanic *sigi-, meaning victory. The second elements of the two names are different, however: in Siegfried, it is Proto-Germanic *-frið, meaning peace; in Sigurd, it is Proto-Germanic *-ward, meaning protection.[1] Although they do not share the same second element, it is clear that surviving Scandinavian written sources held Siegfried to be the continental version of the name they called Sigurd.[2]

The normal form of Siegfried in Middle High German is Sîvrit or Sîfrit, with the *sigi- element contracted. This form of the name had been common even outside of heroic poetry since the ninth century, though the form Sigevrit is also attested, along with the Middle Dutch Zegevrijt. In Early Modern German, the name develops to Seyfrid or Seufrid (spelled Sewfrid). The modern form Siegfried is not attested frequently until the seventeenth century, after which it becomes more common.[3] In modern scholarship, the form Sigfrid is sometimes used.[4]

The Old Norse name Sigurðr is contracted from an original *Sigvǫrðr, which in turn derives from an older *Sigi-warðuR. The Danish form Sivard also derives from this form originally. Hermann Reichert notes that the form of the root -vǫrðr instead of -varðr is only found in the name Sigurd, with other personal names instead using the form -varðr; he suggests that the form -vǫrðr may have had religious significance, whereas -varðr was purely non-religious in meaning.

There are competing theories as to which name is original. Names equivalent to Siegfried are first attested in Anglo-Saxon Kent in the seventh century and become frequent in Anglo-Saxon England in the ninth century. Jan-Dirk Müller argues that this late date of attestation means that it is possible that Sigurd more accurately represents the original name. Wolfgang Haubrichs suggests that the form Siegfried arose in the bilingual Frankish kingdom as a result of romance-language influence on an original name *Sigi-ward. According to the normal phonetic principles, the Germanic name would have become Romance-language *Sigevert, a form which could also represent a Romance-language form of Germanic Sigefred. He further notes that *Sigevert would be a plausible Romance-language form of the name Sigebert from which both names could have arisen. As a second possibility, Haubrichs considers the option that metathesis of the r in *Sigi-ward could have taken place in Anglo-Saxon England, where variation between -frith and -ferth is well documented.

Hermann Reichert, on the other hand, notes that Scandinavian figures who are attested in pre-twelfth-century German, English, and Irish sources as having names equivalent to Siegfried are systematically changed to forms equivalent to Sigurd in later Scandinavian sources. Forms equivalent to Sigurd, on the other hand, do not appear in pre-eleventh-century non-Scandinavian sources, and older Scandinavian sources sometimes call persons Sigfroðr Sigfreðr or Sigfrǫðr who are later called Sigurðr. He argues from this evidence that a form equivalent to Siegfried is the older form of Sigurd's name in Scandinavia as well.

Scandinavian stories about Sigurðr have a strong connection to Germanic mythology. While older scholarship took this to represent the original form of the Sigurðr story, newer scholarship is more inclined to see it as a development of the tradition that is unique to Scandinavia. While some elements of the Scandinavian tradition may indeed be older than the surviving continental witnesses, a good deal seems to have been transformed by the context of the Christianization of Iceland and Scandinavia: the frequent appearance of the heathen gods gives the heroic stories the character of an epoch that is irrevocably over.

Although the earliest attestations for the Scandinavian tradition are pictorial depictions, because these images can only be understood with a knowledge of the stories they depict, they are listed last here.

Prose Edda

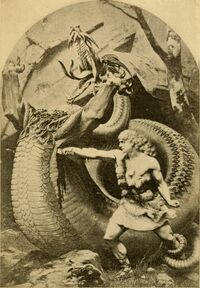

Sigurðr slays the dragon Fáfnir.

Sigurðr is raised at the court of king Hjálprekr, receives the sword Gramr from the smith Reginn, and slays the dragon Fáfnir on Gnitaheiði by lying in a pit and stabbing it in the heart from underneath. Sigurðr tastes the dragon's blood and understands the birds when they say that Reginn will kill him in order to acquire the dragon's gold. He then kills Reginn and takes the hoard of the Nifungs for himself. He rides away with the hoard and then awakens the valkyrja Brynhildr by cutting the armor from her, before coming to king Gjúki's kingdom. There he marries Gjúki's daughter, Guðrún, and helps her brother, Gunnarr, to acquire Brynhildr's hand from her brother Atli. Sigurðr deceives Brynhildr by taking Gunnarr's shape when Gunnarr cannot fulfill the condition that he ride through a wall of flames to wed her; Sigurðr rides through the flames and weds Brynhildr, but does not sleep with her, placing his sword between them in the marriage bed.

Sigurðr and Guðrún have two children, Svanhildr and young Sigmundr. Later, Brynhildr and Guðrún quarrel and Guðrún reveals that Sigurðr was the one who rode through the fire, and shows a ring that Sigurðr took from Brynhildr as proof. Brynhildr then arranges to have Sigurðr killed by Gunnarr's brother Gutþormr. Gutþormr stabs Sigurðr in his sleep, but Sigurðr is able to slice Gutþormr in half by throwing his sword before dying. Gutþormr has also killed Sigurðr's three-year-old son Sigmundr. Brynhildr then kills herself and is burned on the same pyre as Sigurðr.

Poetic Edda

The story of Sigurðr forms the core of the heroic poems collected here. However, the details of Sigurðr's life and death in the various poems contradict each other, so that "the story of Sigurðr does not emerge clearly from the Eddic verse."

The Poetic Edda identifies Sigurðr as a king of the Franks.[5]

Frá dauða Sinfjötla

Sigurðr is born at the end of Frá dauða Sinfjötla; he is the posthumous son of Sigmundr, who dies fighting the sons of Hundingas, and Hjǫrdís. Hjǫrdís is married to the son of Hjálprekr and allowed to raise Sigurðr in Hjálprekr's home.

Grípisspá

In Grípisspá, Sigurðr goes to Grípir, his uncle on his mother's side, in order to hear a prophecy about his life. Grípir tells Sigurðr that he will kill Hundingas's sons, the dragon Fáfnir, and the smith Reginn, acquiring the hoard of the Niflungas. Then he will wake a valkyrja and learn runes from her. Grípir does not want to tell Sigurðr any more, but Sigurðr forces him to continue. He says that Sigurðr will go to the home of Heimir and betroth himself to Brynhildr, but then at the court of King Gjúki he will receive a potion that will make him forget his promise and marry Guðrún. He will then acquire Brynhildr as a wife for Gunnarr and sleep with Brynhildr without having sex with her. Brynhildr will recognize the deception, however, and claim that Sigurðr did sleep with her, and this will cause Gunnarr to have him killed.

Reginsmál

In Reginsmál, the smith Reginn, who is staying at the court of Hjálprekr, tells Sigurðr of a hoard that the gods had had to assemble in order to compensate the family of Ótr, whom they had killed. Fáfnir, Ótr's brother, guards the treasure now and has turned into a dragon. Reginn wants Sigurðr to kill the dragon. He makes the sword Gramr for Sigurðr, but Sigurd chooses to kill Lyngvi and the other sons of Hundingas before he kills the dragon. On his way he is accompanied by Óðinn. After killing the brothers in battle and carving a blood eagle on Lyngvi, Reginn praises Sigurðr's ferocity in battle.

Fáfnismál

In Fáfnismál, Sigurðr accompanies Reginn to Gnitaheiði, where he digs a pit. He stabs Fáfnir through the heart from underneath when the dragon passes over the pit. Fáfnir, before he dies, tells Sigurðr some wisdom and warns him of the curse that lays on the hoard. Once the dragon is dead, Reginn tears out the Fáfnir's heart and tells Sigurðr to cook it. Sigurðr checks whether the heart is done with his finger and burns it. When he puts his finger into his mouth, he can understand the language of the birds, who warn him of Reginn's plan to kill him. He kills the smith and is told by the birds to go to a palace surrounded by flames where the valkyrja Sigrdrífa is asleep. Sigurðr heads there, loading the hoard on his horse.

Sigrdrífumál

In Sigrdrífumál, Sigurðr rides to Hindarfjall, where he finds a wall made of shields. Inside he finds a sleeping woman who is wearing armor that seems to have grown into her skin. Sigurðr cuts open the armor and Sigrdrífa, the valkyrja, wakes up. She teaches him the runes, some magic spells, and gives him advice.

Brot af Sigurðarkviðu

Sigurðr's horse Grani mourns over his body

The poem Brot af Sigurðarkviðu, although the ending is the only left, begins with Hǫgni and Gunnarr discussing whether Sigurðr needs to be murdered. Hǫgni suggests that Brynhildr may be lying that Sigurðr slept with Brynhildr. Then Gutþormr, Gunnarr and Hǫgni's younger brother, murders Sigurðr in the forest, after which Brynhildr admits that Sigurðr never slept with her.

The poem shows the influence of continental Germanic traditions, as it portrays Sigurðr's death in the forest rather than in his bed.

Frá dauða Sigurðar

Frá dauða Sigurðar is a short prose text between the songs. The text mentions that, although the previous song said that Sigurðr was killed in the forest, other songs say he was murdered in bed. German songs say that he was killed in the forest, but the next song in the codex, Guðrúnarqviða in fursta, says that he was killed while going to a þing.

Sigurðarkviða hin skamma

In Sigurðarkviða hin skamma, Sigurðr comes to the court of Gjúki and he, Gunnarr, and Hǫgni swear friendship to each other. Sigurðr marries Guðrún, then acquires Brynhildr for Gunnarr and does not sleep with her. Brynhildr desires Sigurðr, however, and when she cannot have him decides to have him killed. Gutþormr then slays Sigurðr in his bed, but Sigurðr kills him before dying. Brynhildr then kills herself and asks to be burned on the same pyre as Sigurðr.

Vǫlsunga saga

Sigurðr and Brynhildr's first encounter.

In the Vǫlsunga saga, Sigurðr was supposedly the posthumous son of Sigmundr and his second wife, Hjǫrdís. Sigmundr dies in battle when he attacks Óðinn (who is in disguise), and Óðinn shatters Sigmundr's sword. Dying, Sigmundr tells Hjǫrdís of her pregnancy and bequeaths the fragments of his sword to his unborn son.

Hjǫrdís marries King Alf, and then Alf decides to send Sigurðr to Reginn as a foster. Reginn tempts Sigurðr to greed and violence by first asking Sigurðr if he has control over Sigmund's gold. When Sigurðr says that Alf and his family control the gold and will give him anything he desires, Reginn asks Sigurðr why he consents to a lowly position at court. Sigurðr replies that he is treated as an equal by the kings and can get anything he desires. Then Reginn asks Sigurðr why he acts as stable boy to the kings and has no horse of his own. Sigurðr then goes to get a horse. An old man (Óðinn in disguise) advises Sigurðr on choice of horse, and in this way Sigurðr gets Grani, a horse derived from Óðinn's own Sleipnir.

Finally, Reginn tries to tempt Sigurðr by telling him the story of the Ótr's Gold. Reginn's father was Hreiðmarr, and his two brothers were Ótr and Fáfnir. Reginn was a natural at smithing, and Ótr was natural at swimming. Ótr used to swim at Andvari's waterfall, where the dwarf Andvari lived. Andvari often assumed the form of a pike and swam in the pool.

One day, the Æsir saw Ótr with a fish on the banks, thought him an otter, and Loki killed him. They took the carcass to the nearby home of Hreiðmarr to display their catch. Hreiðmarr, Fáfnir, and Reginn seized the Æsir and demanded compensation for the death of Ótr. The compensation was to stuff the body with gold and cover the skin with fine treasures. Loki got the net from the sea giantess Rán, caught Andvari (as a pike), and demanded all of the dwarf's gold. Andvari gave the gold, except for a ring. Loki took this ring, too, although it carried a curse of death on its bearer. The Æsir used this gold to stuff Ótr's body with, and covered his skin in gold. They then covered the last exposed place (a whisker) with the ring of Andvari. Afterwards, Fáfnir killed Hreidmar and took the gold.

Sigurðr agrees to kill Fáfnir, who has turned himself into a dragon in order to be better able to guard the gold. Sigurðr has Reginn make him a sword, which he tests by striking the anvil. The sword shatters, so he has Reginn make another. This also shatters. Finally, Sigurðr has Reginn make a sword out of the fragments that had been left to him by Sigmund. The resulting sword, Gramr, cuts through the anvil. To kill Fáfnir the dragon, Reginn advises him to dig a pit, wait for Fáfnir to walk over it, and then stab the dragon. Odin, posing as an old man, advises Sigurðr to dig trenches also to drain the blood, and to bathe in it after killing the dragon; bathing in Fáfnir's blood confers invulnerability. Sigurðr does so and kills Fáfnir; Sigurðr then bathes in the dragon's blood, which touches all of his body except for one of his shoulders where a leaf was stuck. Reginn then asked Sigurðr to give him Fáfnir's heart for himself. Sigurðr drinks some of Fáfnir's blood and gains the ability to understand the language of birds. Birds advise him to kill Reginn, since Reginn is plotting Sigurðr's death. Sigurðr beheads Reginn, roasts Fáfnir's heart and consumes part of it. This gives him the gift of "wisdom" (prophecy).

Sigurðr met Brynhildr, a "shieldmaiden," after killing Fáfnir. She pledges herself to him but also prophesies his doom and marriage to another. (In Völsunga saga, it is not clear that Brynhildr is a valkyrja or in any way supernatural.)

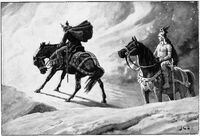

Sigurðr and Gunnarr at the Fire by J. C. Dollman (1909).

Sigurðr went to the court of Heimir, who was married to Bekkhildr, sister of Brynhildr, and then to the court of Gjúki, where he came to live. Gjúki had three sons and one daughter by his wife, Grímhildr. The sons were Gunnarr, Hǫgni and Guttorm, and the daughter was Guðrún. Grímhildr made an "Ale of Forgetfulness" to force Sigurðr to forget Brynhildr, so he could marry Guðrún. Later, Gunnarr wanted to court Brynhildr. Brynhildr's bower was surrounded by flames, and she promised herself only to the man daring enough to go through them. Only Grani, Sigurðr's horse, would do it, and only with Sigurðr on it. Sigurðr exchanged shapes with Gunnarr, rode through the flames, and won Brynhildr for Gunnarr.

Sigurd and Brynhild by C. Butler.

Some time later, Brynhildr taunted Guðrún for having a better husband, and Guðrún explained all that had passed to Brynhildr and explained the deception. For having been deceived and cheated of the husband she had desired, Brynhildr plots revenge. First, she refuses to speak to anyone and withdraws. Eventually, Sigurðr was sent by Gunnarr to see what was wrong, and Brynhildr accuses Sigurðr of taking liberties with her. Gunnarr and Hǫgni plot Sigurðr's death and enchant their brother, Guttorm, to a frenzy to accomplish the deed. Guttorm kills Sigurðr in bed, and Brynhildr kills Sigurðr's three year old son Sigmund (named for Sigurðr's father). Brynhildr then wills herself to die, and builds a funeral pyre for Sigurðr, Sigurðr's son, Guttorm (killed by Sigurðr) and herself.

Sigurðr and Brynhildr had the daughter Áslaug who married Ragnarr Loðbrók. Sigurðr and Guðrún are parents to the twins Sigmundr (named after Sigurðr's father) and Svanhildr.

Tropes

Powers and Abilities

- Superhuman Strength: Sigurðr's immense strength is thanks to being of Óðinn's bloodline. He could have destroyed every weapon Reginn forged for him, untill he received, his father's sword, Gramr from his mother Hjǫrdís. Eventually, he slashed an anvil with Gramr that Reginn had reforged.

- Sword Proficiency

- Enhanced Hearing: After eating Fáfnir's heart, Sigurðr gained a strong sense of hearing. He could learn his foster father Reginn's betrayal scheme and the location of Hindarfjall, where the beautiful Brynhildr lay, by hearing the birds' whispers.

Gallery

Modern description

According to the footnote from the novel Little Briar Rose by Brothers Grimm, the story of Brynhildr and Sigurðr's encounter is the relevant origin for the literature.

Video games

Sigurðr makes his appearance as a Saber-class servant in Fate/Grand Order since the release of the Götterdämmerung Chapter.

Notes

References

- Böldl, Klaus; Preißler, Katharina (2015). "Ballade". Germanische Altertumskunde Online. Berlin, Boston: de Gruyter.

- Byock, Jesse L. (trans.) (1990). The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. Berkeley and Los Angeles, CA: University of California. ISBN 0-520-06904-8.

- Düwel, Klaus (2005). "Sigurddarstellung". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. 28. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 412-422.

- Fichtner, Edward G. (2004). "Sigfrid's Merovingian Origins". Monatshefte. 96 (3): 327-342.

- Gallé, Volker (2011). "Arminius und Siegfried – Die Geschichte eines Irrwegs". In Gallé, Volker (ed.). Arminius und die Deutschen : Dokumentation der Tagung zur Arminiusrezeption am 1. August 2009 im Rahmen der Nibelungenfestspiele Worms. Worms: Worms Verlag. pp. 9–38. ISBN 978-3-936118-76-6.

- Gentry, Francis G.; McConnell, Winder; Müller, Ulrich; Wunderlich, Werner, eds. (2011) [2002]. The Nibelungen Tradition. An Encyclopedia. New York, Abingdon: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-8153-1785-2.

- Gillespie, George T. (1973). Catalogue of Persons Named in German Heroic Literature, 700-1600: Including Named Animals and Objects and Ethnic Names. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 978-0-19-815718-2.

- Grimm, Wilhelm (1867). Die Deutsche Heldensage (2nd ed.). Berlin: Dümmler. Retrieved 24 May 2018.

- Haubrichs, Wolfgang (2000). ""Sigi"-Namen und Nibelungensage". In Chinca, Mark; Heinzle, Joachim; Young, Christopher (eds.). Blütezeit: Festschrift für L. Peter Johnson zum 70. Geburtstag. Tübingen: Niemeyer. pp. 175–206. ISBN 3-484-64018-9.

- Haustein, Jens (2005). "Sigfrid". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. 28. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 380-381.

- Haymes, Edward R. (trans.) (1988). The Saga of Thidrek of Bern. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8240-8489-6.

- Haymes, Edward R.; Samples, Susan T. (1996). Heroic legends of the North: an introduction to the Nibelung and Dietrich cycles. New York: Garland. ISBN 0-8153-0033-6.

- Heinrichs, Heinrich Matthias (1955–1956). "Sivrit - Gernot - Kriemhilt". Zeitschrift für Deutsches Altertum und Deutsche Literatur. 86 (4): 279-289.

- Heinzle, Joachim, ed. (1981–1987). Heldenbuch: nach dem ältesten Druck in Abbildung herausgegeben. Göppingen: Kümmerle. (Facsimile edition of the first printed Heldenbuch (volume 1), together with commentary (volume 2))

- Heinzle, Joachim, ed. (2013). Das Nibelungenlied und die Klage. Nach der Handschrift 857 der Stiftsbibliothek St. Gallen. Mittelhochdeutscher Text, Übersetzung und Kommentar. Berlin: Deutscher Klassiker Verlag. ISBN 978-3-618-66120-7.

- Höfler, Otto (1961). Siegfried, Arminius und die Symbolik: mit einem historischen Anhang über die Varusschlacht. Heidelberg: Winter.

- Holzapfel, Otto (Otto Holzapfel), ed. (1974). Die dänischen Nibelungenballaden: Texte und Kommentare. Göppingen: Kümmerle. ISBN 3-87452-237-7.

- Lee, Christina (2007). "Children of Darkness: Arminius/Siegfried in Germany". In Glosecki, Stephen O. (ed.). Myth in Early Northwest Europe. Tempe, Arizona: Brepols. pp. 281–306. ISBN 978-0-86698-365-5.

- Lienert, Elisabeth (2015). Mittelhochdeutsche Heldenepik. Berlin: Erich Schmidt. ISBN 978-3-503-15573-6.

- McKinnell, John (2015). "The Sigmundr / Sigurðr Story in an Anglo-Saxon and Anglo-Norse Context". In Mundal, Else (ed.). Medieval Nordic Literature in its European Context. Oslo: Dreyers Forlag. pp. 50–77. ISBN 978-82-8265-072-4.

- Millet, Victor (2008). Germanische Heldendichtung im Mittelalter. Berlin, New York: de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-020102-4.

- Müller, Jan-Dirk (2009). Das Nibelungenlied (3 ed.). Berlin: Erich Schmidt.

- Larrington, Carolyne (trans.) (2014). The Poetic Edda: Revised Edition. Oxford: Oxford University. ISBN 978-0-19-967534-0.

- Reichert, Hermann (2008). "Zum Namen des Drachentöters. Siegfried - Sigurd - Sigmund - Ragnar". In Ludwig, Uwe; Schilp, Thomas (eds.). Nomen et fraternitas : Festschrift für Dieter Geuenich zum 65. Geburtstag. Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 131–168. ISBN 978-3-11-020238-0.

- Sprenger, Ulrike (2000). "Jungsigurddichtung". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. 16. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 126–129.

- Sturluson, Snorri (2005). The Prose Edda: Norse Mythology. Translated by Byock, Jesse L. New York, London: Penguin Books.

- Taranu, Catalin (2015). "Who Was the Original Dragon-slayer of the Nibelung Cycle?". Viator. 46 (2): 23-40.

- Uecker, Heiko (1972). Germanische Heldensage. Stuttgart: Metzler. ISBN 3-476-10106-1.

- Uspenskij, Fjodor. 2012. The Talk of the Tits: Some Notes on the Death of Sigurðr Fáfnisbani in Norna Gests þáttr. The Retrospective Methods Network (RMN) Newsletter: Approaching Methodology. No. 5, December 2012. Pp. 10–14.

- Würth, Stephanie (2005). "Sigurdlieder". In Beck, Heinrich; Geuenich, Dieter; Steuer, Heiko (eds.). Reallexikon der Germanischen Altertumskunde. 28. New York/Berlin: de Gruyter. pp. 424–426.

| Heroes in Norse mythology | |

|---|---|

| Angantýr Arngrímsson • Arngrímr • Áslaug • Bjǫrn Járnsíða • Bǫðvarr Bjarki • Egill • Erpr • Gjúki • Guðmundr • Hagbarðr • Haki • Hamðir • Heiðrekr • Helgi Haddingjaskati • Helgi Hundingsbane • Hervǫr Angantýsdóttir • Hervǫr Heiðreksdóttir • Hildólfr • Hjálmarr and Ingibjǫrg • Hlǫðr • Hrólfr Kraki • Hǫðbroddr • Karl Hundason • Níðuðr • Palnatóki • Ragnarr Loðbrók • Ring II • Rerir • Sigi • Sigmundr • Signý • Sigurðr • Sigurðr Hjort • Sinfjǫtli • Starkaðr • Styrbjǫrn Sterki • Svafrlami • Svanhildr • Svipdagr • Sæmingr • Sǫrli • Vésteinn • Víkarr • Vikingr • Vǫlsungr • Yrsa • Þiðrekr af Bern • Ǫrvar-Oddr | |